‘Frans Hals is a colourist among the colourists, a colourist like Veronese, like Rubens, like Delacroix, like Velázquez… But – tell me – black and white, may one use them or not? Are they forbidden fruit? I think not. Frans Hals must have had twenty-seven blacks.’ [Van Gogh, letter to his brother Theo, 1885]

Pure Impressionism shunned black. Van Gogh did not. Black is not uniform. Stand before a portrait by FRANS HALS (1582–1666) of a finely dressed gent and marvel at the subtlety of the French black silk. A few quick broad strokes, minute changes of tone. Van Gogh rejoiced in their difference ‘from the paintings – so many of them – where everything has been carefully smoothed out in the same way.’

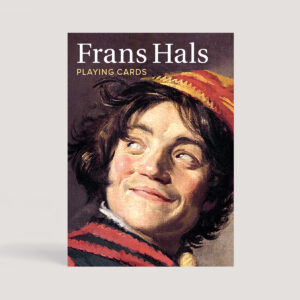

Hals’ ‘rough style’ was based on late Titian and Tintoretto. It was the antithesis of the polished veneer of Dutch contemporaries like Gerrit Dou and van Mieris. It conveyed movement, vivacity. Hals painted no landscapes, no still lifes, though these were the stuff of Dutch Golden Age painting. He just did people, as Van Gogh noted – ‘Portraits of soldiers, gatherings of officers…he painted the tipsy drinker, the old fishwife full of a witch’s mirth, the beautiful Gypsy whore, babies in swaddling clothes, the gallant, bon vivant gentleman…’ His tone, both of shade and of sometimes risqué content, owes much to Caravaggio.

Hals was born in the Flemish city of Antwerp. But in 1585, after a siege, it fell to Spain and his family fled to Haarlem, a textile centre (Hals’ father was a clothmaker). Frans was apprenticed to another Flemish émigré, the artist Karel van Mander. Hals returned briefly to Antwerp in 1616, where he absorbed the panache of Rubens. But thereafter he rarely left Haarlem, where he early became the master of the group painting. Status-hungry bourgeois bigwigs paid to have themselves included – and Hals had to weigh puffed-up egos against compositional balance.

His portraits caught sitters, mostly men, in moods, in mid-gesture, as in a photograph, portrayed in their confident finery. Hals conveys their vitality, their smugness, but attempts neither the psychological insight of Rembrandt, nor the merciless exposure of Velázquez. If his technique has artifice, there is nothing subtle in their depiction, with their blatant self-regard; nothing subtle in the happy drunks he portrays (to reassure his patrons that the lower orders are content in their lot). The subtlety is in his alchemy; how this virtuoso of the visible brushstroke transforms a few flicks of paint into a smile or a ruff. Hals knew most of his sitters, and it shows.

His portraits caught sitters, mostly men, in moods, in mid-gesture, as in a photograph, portrayed in their confident finery. Hals conveys their vitality, their smugness, but attempts neither the psychological insight of Rembrandt, nor the merciless exposure of Velázquez. If his technique has artifice, there is nothing subtle in their depiction, with their blatant self-regard; nothing subtle in the happy drunks he portrays (to reassure his patrons that the lower orders are content in their lot). The subtlety is in his alchemy; how this virtuoso of the visible brushstroke transforms a few flicks of paint into a smile or a ruff. Hals knew most of his sitters, and it shows.

Kenneth Clark, the great art historian, called Hals’ work ‘revoltingly cheerful and horribly skilful’; but he loved ‘their unthinking conviviality’. Perhaps Clark was disturbed by Hals blurring the distinction between genre scenes and portraits. His subjects often seem to have popped from the tavern to the studio, still full of beery bonhomie.

Hals married twice (his first wife died). His second wife was regularly arrested for fighting. He had fourteen children (though many died young). Despite success, he struggled with debt all his life. At the end, his style became less fashionable and the city supported him. Hals’ technique loosened as he got older, but the limited palette remained unchanged.

After his death, a biographer dismissed him as a drunken slob unable to finish his pictures. His reputation collapsed – until the 19C when French art critic Théophile Thoré recognised Hals as a genius (‘his brushstrokes make their mark, aimed precisely and wittily where they should’). Hals’ rehabilitation was confirmed when in 1865 the Marquess of Hertford paid six times the estimate for The Laughing Cavalier. It shows a rich young man dressed in the latest sumptuous French fashions. The title is a misnomer: the sitter is neither a cavalier nor laughing. Unlike the bravura urgency of other portraits, it is meticulously painted. But his knowing expression reveals nothing.

Van Gogh noted that whereas Rembrandt was mystical and mysterious, Hals ‘always remains on earth.’ He makes you smile. Van Gogh loved his sureness – ‘Paint in one go, as far as possible in one go.’ The flashes of paint are about communication. Merchants, or pub bores, pose; but it is not to fix them for all time, only for a moment. They are a record of men, but also of encounters. And what exuberance they convey. A contemporary wrote that Hals ‘excels almost everyone…His paintings are imbued with such force and vitality that he seems to surpass nature herself with his brush… they seem to breathe and live.’ (T. Schrevelius, 1648). Vincent put it more simply – ‘What a joy it is to see a Frans Hals.’