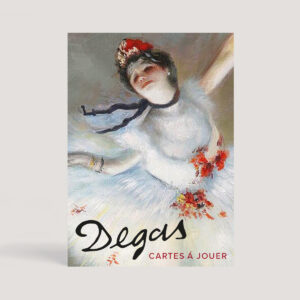

EDGAR DEGAS (1834-1917)

L’Absinthe (1875/6) may be about a powerful spirit made from wormwood (the ‘Green Fairy’) but it is art, not sociology. Phylloxera had devastated French vineyards, which made wine expensive. The cheapest way to oblivion was Absinthe. The picture is the essence of Degas: lowlifes, distraction, jagged planes, subtle palette. Sadness. And precise drawing (‘I am a colourist with line’). Space is suggested, not constructed; the zig-zags define it. ‘I thirst for order,’ he said. The lady’s splayed feet hint at wooziness. The bohemian with bloodshot eyes nurses a Mazagran, an Algerian hangover cure. This seeming snapshot of urban life is, like all Degas’ work, suffused with artifice. ‘No art is less spontaneous than mine. What I do is the result of reflection and study of the Old Masters. Of inspiration, spontaneity, temperament…I know nothing’. The scene is staged. The drinkers are Degas’ friends, Ellen Andrée, a star of the Folies-Bergère; and Marcellin Desboutin, a fellow painter (Degas had to state publicly that they were not actually alcoholics). The café is La Nouvelle Athènes on Place Pigalle in Montmartre; Courbet and Manet drank there. Degas said he wished to make ‘portraits of people in typical familiar poses…paying particular attention to making their faces as expressive as their bodies’.

L’Absinthe (1875/6) may be about a powerful spirit made from wormwood (the ‘Green Fairy’) but it is art, not sociology. Phylloxera had devastated French vineyards, which made wine expensive. The cheapest way to oblivion was Absinthe. The picture is the essence of Degas: lowlifes, distraction, jagged planes, subtle palette. Sadness. And precise drawing (‘I am a colourist with line’). Space is suggested, not constructed; the zig-zags define it. ‘I thirst for order,’ he said. The lady’s splayed feet hint at wooziness. The bohemian with bloodshot eyes nurses a Mazagran, an Algerian hangover cure. This seeming snapshot of urban life is, like all Degas’ work, suffused with artifice. ‘No art is less spontaneous than mine. What I do is the result of reflection and study of the Old Masters. Of inspiration, spontaneity, temperament…I know nothing’. The scene is staged. The drinkers are Degas’ friends, Ellen Andrée, a star of the Folies-Bergère; and Marcellin Desboutin, a fellow painter (Degas had to state publicly that they were not actually alcoholics). The café is La Nouvelle Athènes on Place Pigalle in Montmartre; Courbet and Manet drank there. Degas said he wished to make ‘portraits of people in typical familiar poses…paying particular attention to making their faces as expressive as their bodies’.

French critics called the picture ugly and disgusting. The English thought it uncouth, and typical of French decadence. George Moore dismissed the woman shown – ‘What a whore!’

Despite being one of the founders of Impressionism, Degas called himself a ‘Realist’. He showed little interest in plein-air landscapes, preferring scenes in theatres and cafés in the glare of limelight. Born into a rich banking family, he was educated in the classics in Paris, and encouraged to visit museums. He trained under the academic Louis Lamothe, who emphasised the primacy of drawing. Trips Degas made to Italy in the 1850s had a profound influence.

But his passion was not for the staid, the classical, the heroic; but for scenes from modern life: the racecourse, cafés, concerts, bars, ballet. Women washing. ‘I show them without their coquetry…as if I looked through the keyhole.’

Degas was influenced by the asymmetry and cropping of Japanese prints and Italian Mannerism. His ballet pictures (totalling over 1500) are usually viewed from strange vantage points. They are not portraits, but studies of movement, of concentration; he was fascinated by the dancers’ painful discipline. I once heard the ballerina Darcey Bussell extol Dagas’ extraordinary understanding of the intricacies, the vocabulary, of ballet poses, how exact his pictures were.

His nudes, particularly in the bath, squat awkwardly but the steep perspective lends solidity. Before 1880, he mostly used oils for completed works; afterwards he preferred pastels. Around 1890 his eyesight began to fail (caused by an injury during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1), after which he focused on dancers and nudes, and women bathing, turning to sculpture as his eyes weakened. Degas had always been morose, and became more so. But his art is not that of a curmudgeon. It is enigmatic. ‘Beauty is a mystery,’ he said. His genius was to find beauty in L’Absinthe, two drunks bored in a bar.