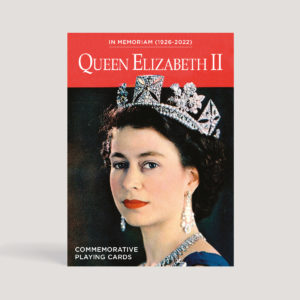

HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH II (1926-2022)

The late QUEEN ELIZABETH II was not born to rule. Her father, the stammering, diffident Duke of York was thrust on the throne as George VI when his elder brother Edward VIII chose Wallis Simpson over duty, and abdicated in 1936. It was just as well for the nation. Edward’s sympathy for Hitler was apparent, particularly to the PM Stanley Baldwin, whose subtle machinations speeded Edward’s exit. George was a good king and good for Britain but the strain of kingship (and heavy smoking) ruined his health and he died in 1952 while Princess Elizabeth, who had married the handsome, penniless Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark in 1947, was in Kenya. She now became Queen Elizabeth II, and was crowned in Westminster Abbey in June 1953 on a memorably wet day. While the event was being planned she had to deal with her sister Margaret’s proposal to marry the divorced Group Captain Peter Townsend. The Queen handled this constitutional (and PR) crisis with assurance, advising delay (in the hope that ardour would cool) and pointing out that Margaret would lose royal privileges and rights of succession. Ardour cooled.

The late QUEEN ELIZABETH II was not born to rule. Her father, the stammering, diffident Duke of York was thrust on the throne as George VI when his elder brother Edward VIII chose Wallis Simpson over duty, and abdicated in 1936. It was just as well for the nation. Edward’s sympathy for Hitler was apparent, particularly to the PM Stanley Baldwin, whose subtle machinations speeded Edward’s exit. George was a good king and good for Britain but the strain of kingship (and heavy smoking) ruined his health and he died in 1952 while Princess Elizabeth, who had married the handsome, penniless Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark in 1947, was in Kenya. She now became Queen Elizabeth II, and was crowned in Westminster Abbey in June 1953 on a memorably wet day. While the event was being planned she had to deal with her sister Margaret’s proposal to marry the divorced Group Captain Peter Townsend. The Queen handled this constitutional (and PR) crisis with assurance, advising delay (in the hope that ardour would cool) and pointing out that Margaret would lose royal privileges and rights of succession. Ardour cooled.

Her Majesty’s marriage endured. She and Prince Philip (who died in 2021) were both dutiful and patriotic (the mostly German Prince Philip became a naturalised British subject in 1947). They loved sport, but different ones. She had a passion for horse racing – particularly the breeding side – and he loved cricket, polo and carriage driving. She was reserved and tactful. He was not. A trait he shared with his daughter Anne.

During her reign dramatic shifts in society threatened to engulf the monarchy. Sixties iconoclasm, independence movements in the dominions, anti-élitism at home and the example of European royals swapping the Rolls for a Raleigh all made her regal style seem outdated. Her public relations ‘experts’ advised a ‘fly-on-the-wall’ TV documentary showing the royal family chatting, watching telly, barbecuing. Royal Family (1969) was a disaster. The mystery of monarchy, which depends on distance, was shattered.

But gradually the Queen restored respect by simply doing what she did best, her constitutional duty as Head of State. She steered a subtle course, adapting when necessary. This was key to her successful reign, which saw 15 Prime Ministers.

But gradually the Queen restored respect by simply doing what she did best, her constitutional duty as Head of State. She steered a subtle course, adapting when necessary. This was key to her successful reign, which saw 15 Prime Ministers.

Perhaps the biggest strain she faced was the collapse of her children’s marriages, the bitter fighting between the Charles and Diana camps, and Fergie’s eccentric behaviour (‘vulgar, vulgar, vulgar’ the courtier Lord Charteris called it). But the death of Princess Diana in 1997 threatened greater damage and the Queen and her advisors responded sluggishly. The world had changed. They had not sensed a new, more ‘emotive’ way with grief. The Royal Family and Diana’s sons remained in Scotland while near hysteria erupted in London (‘Where is the Queen when the country needs her?’ – The Sun). No flag flew at half-mast from Buckingham Palace. But then, characteristically, she reversed her position, flew the flag at half-mast and returned with the boys to London.

She broadcast an emotional address, in which she conceded ‘there are lessons to be drawn from Diana’s life and from the extraordinary and moving reaction to her death.’ She had the courage to admit she was wrong. Her bravery was not just moral. I witnessed the moment in 1981 when a madman fired six shots at the Queen as she rode down The Mall to the Trooping the Colour ceremony. She did not know they were blanks. She did not flinch. She was a noble Queen indeed. When she died at Balmoral on 8 September 2022, Elizabeth II was the longest-living and longest-reigning British monarch. As Boris Johnson said: ‘It is in the depths of our grief that we understand why we loved her so much.’

She broadcast an emotional address, in which she conceded ‘there are lessons to be drawn from Diana’s life and from the extraordinary and moving reaction to her death.’ She had the courage to admit she was wrong. Her bravery was not just moral. I witnessed the moment in 1981 when a madman fired six shots at the Queen as she rode down The Mall to the Trooping the Colour ceremony. She did not know they were blanks. She did not flinch. She was a noble Queen indeed. When she died at Balmoral on 8 September 2022, Elizabeth II was the longest-living and longest-reigning British monarch. As Boris Johnson said: ‘It is in the depths of our grief that we understand why we loved her so much.’