MARK ROTHKO: A deceptive stillness

‘I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, doom…. there is no such thing as a good painting about nothing.’

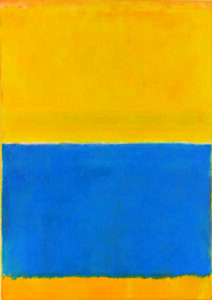

MARK ROTHKO (born Marcus Rothkovitch in Latvia, 1903) brought something new to the post-war Abstract Expressionist school – emotion. He spent a lifetime exploring the limitless possibilities of layering expressive coloured rectangles onto fields of compatible colour (the result became known as Colour Field Painting).

He took up painting in New York in 1925, and was essentially self-taught. He spurned bravado techniques like violent brushstrokes or paint splattering for a more restrained method and style, juxtaposing large areas of soft-edged colours in a vertical frame. His paintings – which he simplified over the years – are large, but intimate. The subtle nuances of colour are most manifest in the series of 14 immense canvases in the Rothko Chapel in Houston. They are almost, but not quite, monochrome, with deep glowing browns, maroons and blacks – a dark intensity perhaps betraying the mysticism, and introspection, of his later years. He killed himself in 1970.

He wanted to make paintings that would provoke tears. ‘A lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures… If you are moved only by their colour relationships, then you miss the point.’ For Rothko, art was a profound form of communication; and a moral act.

Rothko cared about the effect his art had on others. He craved a certain reaction, an appreciation removed from the purely decorative. When private buyers came to his studio in search of a picture he would deny them if their reaction was ‘wrong’. A collector once rejected the offer of a painting in burgundy, plum and black. ‘Mr. Rothko, I’d like a happy painting. A red painting, an orange painting, a yellow painting. A happy painting.’ He replied: ‘Red, orange, yellow – isn’t that the colour of an inferno?’

The conflict between his art and public perception came to a head with the 1958 commission for a series of paintings for The Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building in New York. It supplied him with a new dimension. Rothko’s desire to become immersed in the spaces of his paintings became increasingly dominant. The commission provided the most literal means (a ‘jointed scheme’ he called it) – canvases would surround the viewer as murals. And it was the first time that Rothko would paint a properly unified series. But Rothko was ambivalent, torn between his hatred of the greed, the frivolity, of capitalism and wanting to create a special place for his art. He eventually created 30 murals, dark and voluptuous. Dark paintings – in burgundy, plum and black – were not necessarily evidence of his final depression, he had much earlier turned at times to darkness.

The conflict between his art and public perception came to a head with the 1958 commission for a series of paintings for The Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building in New York. It supplied him with a new dimension. Rothko’s desire to become immersed in the spaces of his paintings became increasingly dominant. The commission provided the most literal means (a ‘jointed scheme’ he called it) – canvases would surround the viewer as murals. And it was the first time that Rothko would paint a properly unified series. But Rothko was ambivalent, torn between his hatred of the greed, the frivolity, of capitalism and wanting to create a special place for his art. He eventually created 30 murals, dark and voluptuous. Dark paintings – in burgundy, plum and black – were not necessarily evidence of his final depression, he had much earlier turned at times to darkness.

Before the Seagram pictures were hung Rothko dined at the restaurant with his wife Mell. He was appalled. ‘Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those kind of prices will never look at a painting of mine.’ He tore up the cheque. Eventually he gave a number of the pictures to the Tate.

If his last paintings are expressions of foreboding, then what happened after his death was almost a metaphor for despair – and for the corruption of art that he fought against. His two children were defrauded of their inheritance by three executors and his gallery. After eleven years of ruinous litigation they won. Many of Rothko’s paintings now grace public collections and can be appreciated for what they are and what they represent. Do not be seduced by their stillness, their silence. As Rothko said: ‘I would like to say to those who think of my pictures as serene, whether in friendship or mere observation, that I have imprisoned the most utter violence in every inch of their surface.’