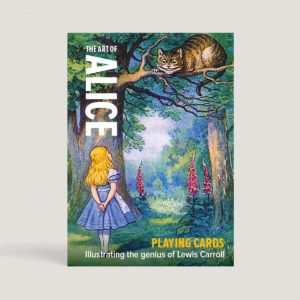

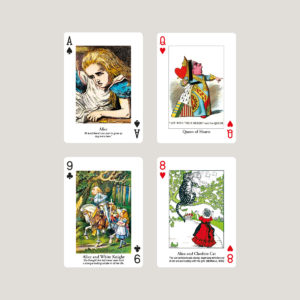

Picturing Alice. ‘What is the use of a book,’ thought Alice, ‘without pictures or conversations?’ Quite so. There have been hundreds of illustrators for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871); but John Tenniel is the greatest (and the best known). He established the image of Alice. Yet he was not the first. That was Carroll himself, whose real name was Charles Dodgson (1832-98), a shy but brilliant maths tutor at Christ Church, Oxford. He was also a logician, Anglican deacon and photographer. And an inventor (of a traveling chessboard, and an early form of Scrabble). A stammer (‘my hesitation’ he called it) made him awkward with adults but happy with children. His narrative was inspired by a rowing trip on the Thames he took in 1862 with the three Liddell sisters, daughters of Christ Church’s dean. He told the youngest daughter, Alice, a story and when he dropped her back at the deanery, she begged him to write it down. He did. But the book’s subtleties – its play with logic and parodies – took two years to complete. ‘The whole thing is a dream,’ explained Carroll. Above all, it is a masterpiece of the (very English) genre of literary nonsense, of inspired insanity (‘We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad,’ says the Cheshire Cat). In 1864, Dodgson presented Alice with his illustrated manuscript entitled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. A friend saw it by chance and urged publication. Now called Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland it was first published by Macmillan in 1865, but practically all 2000 copies were withdrawn as Tenniel, the (uncompromising) Punch illustrator chosen by Carroll, was unhappy with the printing (only 22 copies of that first edition are known to exist). Carroll funded the new edition (1866). The next is dated 1866.

Picturing Alice. ‘What is the use of a book,’ thought Alice, ‘without pictures or conversations?’ Quite so. There have been hundreds of illustrators for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871); but John Tenniel is the greatest (and the best known). He established the image of Alice. Yet he was not the first. That was Carroll himself, whose real name was Charles Dodgson (1832-98), a shy but brilliant maths tutor at Christ Church, Oxford. He was also a logician, Anglican deacon and photographer. And an inventor (of a traveling chessboard, and an early form of Scrabble). A stammer (‘my hesitation’ he called it) made him awkward with adults but happy with children. His narrative was inspired by a rowing trip on the Thames he took in 1862 with the three Liddell sisters, daughters of Christ Church’s dean. He told the youngest daughter, Alice, a story and when he dropped her back at the deanery, she begged him to write it down. He did. But the book’s subtleties – its play with logic and parodies – took two years to complete. ‘The whole thing is a dream,’ explained Carroll. Above all, it is a masterpiece of the (very English) genre of literary nonsense, of inspired insanity (‘We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad,’ says the Cheshire Cat). In 1864, Dodgson presented Alice with his illustrated manuscript entitled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. A friend saw it by chance and urged publication. Now called Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland it was first published by Macmillan in 1865, but practically all 2000 copies were withdrawn as Tenniel, the (uncompromising) Punch illustrator chosen by Carroll, was unhappy with the printing (only 22 copies of that first edition are known to exist). Carroll funded the new edition (1866). The next is dated 1866.

In the 1890s, Beatrix Potter, of Peter Rabbit fame, created six illustrations although none appeared in book form. Copyright restraint prevented new illustrated editions until the American Blanche McManus’s artwork for a NY publisher for both Alice books (1899/1900), in Arts and Crafts mode (Bertram Goodhue, an American architect, had illustrated an Alice play in similar style in 1898). British copyright of Alice’s Adventures expired in 1907; about 20 illustrated editions appeared in the next two years alone (Through the Looking-Glass copyright ran out in 1948). Arthur Rackham reinterpreted Alice (1907) in fantastic, dreamlike drawings where line is key and colour muted. By 1932, Alice was reprinted over 98,000 times! The first rip-off was produced in New York in 1882 – a rather crude card game.

Colour editions of Tenniel’s work appeared quite early. In 1881, Carroll suggested to Macmillan a ‘Nursery Edition’ of Alice with colour pictures – ‘to be read by Children aged from Nought to Five. To be read? Nay, not so! Say rather to be thumbed, to be cooed over, to be dogs’-eared, to be rumpled, to be kissed …’ Carroll rewrote Alice, simplifying the text, while Tenniel redrew, enlarged and coloured twenty illustrations. It was eventually printed in 1890 after the author, ever the perfectionist, rejected the first 10,0000 sheets because the pictures were too gaudy. Alice’s famous dress was yellow; but in 1901 Harry G. Theaker coloured sixteen of Tenniel’s plates for a one-volume Alice edition and her dress was blue – and has remained so in the popular mind ever since. Alices change to fit fashion: Bessie Gutmann created an Art Nouveau Alice in 1907, with long, swept up hair. Willy Pogany’s 1929 illustrations, a complete break from Tenniel, show a Jazz Age flapper, lanky and sporty. Mervyn Peake’s illustrations (1946) are nicely sinister and capture Carroll’s surreal essence but through the lens of the 20C. Philp Gough’s decorative plates (1949), in the manner of Rex Whistler, bring Rococo flair and elegance; while Disney’s Alice (1951) sacrifices personality to prettiness. Dali tried his hand at Alice.

Colour editions of Tenniel’s work appeared quite early. In 1881, Carroll suggested to Macmillan a ‘Nursery Edition’ of Alice with colour pictures – ‘to be read by Children aged from Nought to Five. To be read? Nay, not so! Say rather to be thumbed, to be cooed over, to be dogs’-eared, to be rumpled, to be kissed …’ Carroll rewrote Alice, simplifying the text, while Tenniel redrew, enlarged and coloured twenty illustrations. It was eventually printed in 1890 after the author, ever the perfectionist, rejected the first 10,0000 sheets because the pictures were too gaudy. Alice’s famous dress was yellow; but in 1901 Harry G. Theaker coloured sixteen of Tenniel’s plates for a one-volume Alice edition and her dress was blue – and has remained so in the popular mind ever since. Alices change to fit fashion: Bessie Gutmann created an Art Nouveau Alice in 1907, with long, swept up hair. Willy Pogany’s 1929 illustrations, a complete break from Tenniel, show a Jazz Age flapper, lanky and sporty. Mervyn Peake’s illustrations (1946) are nicely sinister and capture Carroll’s surreal essence but through the lens of the 20C. Philp Gough’s decorative plates (1949), in the manner of Rex Whistler, bring Rococo flair and elegance; while Disney’s Alice (1951) sacrifices personality to prettiness. Dali tried his hand at Alice.  The book appeals to adults and children, with its subtle wit and charm. Dali does neither. Tenniel remains unsurpassed. He realised that a literary joke needs deadpan illustration, or the humour is lost. Comedy is a serious business and required the line of an old master (his White Knight is based on Dürer). The Jabberwock, inspired by Uccello, is properly absurd but not a cartoon baddy. Tenniel (who had only one good eye – ‘but what an eye!’) simply drew what Carroll wrote – ‘The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame / Came whiffling through the tulgey wood / And burbled as it came!’ Carroll noted that Tenniel ‘resolutely refused to use a model’ – but then a Jabberwock might not sit still.

The book appeals to adults and children, with its subtle wit and charm. Dali does neither. Tenniel remains unsurpassed. He realised that a literary joke needs deadpan illustration, or the humour is lost. Comedy is a serious business and required the line of an old master (his White Knight is based on Dürer). The Jabberwock, inspired by Uccello, is properly absurd but not a cartoon baddy. Tenniel (who had only one good eye – ‘but what an eye!’) simply drew what Carroll wrote – ‘The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame / Came whiffling through the tulgey wood / And burbled as it came!’ Carroll noted that Tenniel ‘resolutely refused to use a model’ – but then a Jabberwock might not sit still.