Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) was an artist at ease with the demi-monde he frequented: the world of the night, of prostitutes, absinthe drinkers and can-can dancers. Eventually it would kill him. He died of syphilis and alcoholism. ‘His paintings were almost entirely painted in absinthe,’ remarked his contemporary Gustav Moreau.

But he was not at ease with himself. He was mocked for his height. He was a mere four feet, eight inches (through a genetic condition – the result of his parents being first cousins). His aristocratic birth (in Albi, SW France) came with expectations of social hauteur he could not fulfil. ‘I am neither tall nor beautiful’ (‘but life is beautiful,’ he added). The painter Édouard Vuillard said that ‘Lautrec was a physical freak, an aristocrat cut off from his kind by his grotesque appearance. He found an affinity between his condition and the moral penury of the prostitute.’ And they were often petite. ‘I have found girls of my own size! Nowhere else do I feel so much at home.’

He walked with a cane, in which a phial of absinthe was secreted. [He even kept a tame bird which ‘developed a taste for the stuff’.] His father, the Comte de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa, grumbled – ‘Why doesn’t he go to England? They scarcely notice drunks there.’

His precocity was noticed by a painter friend of his father’s, René Princeteau (a deaf mute) and in 1871 Princeteau tutored him, taught him technique. Their infirmities cemented their friendship. In 1882 Lautrec moved to Paris to study. He met van Gogh, a fellow student at Fernand Cormon’s academic atelier. His influence, like that of Degas (‘I prefer Lautrec,’ said Cézanne), is visible in Lautrec’s early painting. And, in 1885, he met the circus performer, model and artist Suzanne Valadon. She saw only his talent and wit. They became lovers. He painted her, encouraged her. When the relationship ended, she attempted suicide.

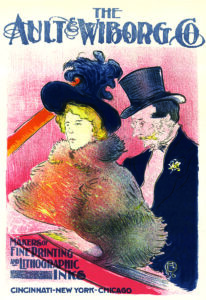

In 1884 Lautrec set up his own studio in bohemian Montmartre. He was soon in demand – for the brilliance of his line (‘I have always been a pencil’). People were what interested him, scenery served only to understand the figure. ‘The pure landscape painter is a barbarian.’ Besides… ‘I am quite incapable of making landscapes, my trees look like spinach.’ The Moulin Rouge (opened 1889) commissioned paintings and posters of the singer Yvette Guilbert, the dancer Louise Weber (La Goulue – ‘The Glutton’, who created the can-can) and the dancer Jane Avril (‘I owe him my fame,’ she said). Guilbert and Avril both feature in his 1892 lithograph, Le Divan Japonais, which was a Lautrec haunt (‘a second-hand version of Japan, a high-class swindle’, according to one critic). Aristide Bruant, a cabaret owner and singer of debauched songs, who ‘strolled Montmartre like a moving sign’, also commissioned designs – of himself – to festoon his club (‘Magnificent posters!’ exclaimed the poet Verhaeren). They derive from Japanese kabuki prints, woodcuts of actors. Lautrec’s posters were everywhere. They were ‘the frescoes of the crowd’. Braque used to peel them off Paris walls.

Although his mother (who separated from his father) sent him an allowance, Lautrec prospered from his mastery of the new art of lithography. In style, he emulated Japanese ukiyo-e prints, with their large flat areas of colour, and strong outlines. He developed the crachis technique of spattering ink onto the lithographic stone’s surface to create atmospheric mists of colour. His posters of cabaret stars (‘an astonishing human menagerie!’ – Octave Uzanne) created the cult of celebrity. They influenced Picasso, and Warhol. Lautrec had a stroke in 1901. His father, an absent figure in his son’s life, came to his bedside. Lautrec said: ‘I knew, papa, that you wouldn’t miss the kill.’ His father was silent. ‘The old fool!’ muttered Lautrec, and died.

Although his mother (who separated from his father) sent him an allowance, Lautrec prospered from his mastery of the new art of lithography. In style, he emulated Japanese ukiyo-e prints, with their large flat areas of colour, and strong outlines. He developed the crachis technique of spattering ink onto the lithographic stone’s surface to create atmospheric mists of colour. His posters of cabaret stars (‘an astonishing human menagerie!’ – Octave Uzanne) created the cult of celebrity. They influenced Picasso, and Warhol. Lautrec had a stroke in 1901. His father, an absent figure in his son’s life, came to his bedside. Lautrec said: ‘I knew, papa, that you wouldn’t miss the kill.’ His father was silent. ‘The old fool!’ muttered Lautrec, and died.

The critic Mellerio wrote that Lautrec ‘analyzed vice with unusual perceptiveness.’ Jules Renard, whose bestiary Lautrec illustrated, put it simply: Lautrec ‘wanted a life with theatre and a theatre with life.’