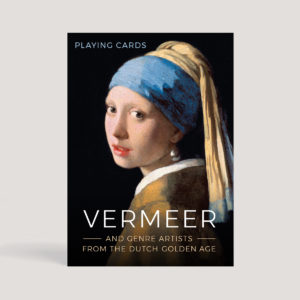

VERMEER AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF DUTCH ART

Bertrand Russell wrote: ‘It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of Holland in the 17th century, as the one country where there was freedom of speculation… Spinoza would hardly have been allowed to do his work in any other country.’ Alongside freedom to speculate, to philosophise, there was freedom to reinvent art, unencumbered by church or state. Realism, particularly in genre painting, flourished in the seven northern provinces of the Dutch Republic in the 17C, and was the key feature of Dutch Golden Age painting – roughly 1568, the start of the rebellion against Spain, to 1672 (‘the year of disaster’), the French invasion, which collapsed the economy.

PAINTING IN THE DUTCH REPUBLIC

The new Republic had prospered (particularly after the end of the Spanish war in 1648), due to the Protestant work ethic, cheap energy from windmills and peat, efficient transport (via canal) and low interest rates determined by the Bank of Amsterdam, effectively, the first central bank. The Republic dominated trade in the Baltic; and the Dutch East India Company, the first global conglomerate, enjoyed a monopoly on Asian trade. Freed from the diktats of Catholicism and monarchy, Dutch art evolved along free market principles. Not for them flamboyant history painting, nor the Counter Reformation grandeur of Flemish masters from the south like Rubens (anyway, Calvinism forbade religious pictures in church). State patronage ended with the early death of the quasi-sovereign stadholder in 1650.

The new Republic had prospered (particularly after the end of the Spanish war in 1648), due to the Protestant work ethic, cheap energy from windmills and peat, efficient transport (via canal) and low interest rates determined by the Bank of Amsterdam, effectively, the first central bank. The Republic dominated trade in the Baltic; and the Dutch East India Company, the first global conglomerate, enjoyed a monopoly on Asian trade. Freed from the diktats of Catholicism and monarchy, Dutch art evolved along free market principles. Not for them flamboyant history painting, nor the Counter Reformation grandeur of Flemish masters from the south like Rubens (anyway, Calvinism forbade religious pictures in church). State patronage ended with the early death of the quasi-sovereign stadholder in 1650.

Paintings in the Netherlands were suddenly everywhere: walls were smothered with them, often bought as investments by humble tradesmen who now had spare cash; but although most were affordable, there were exceptions – Rembrandt’s pupil Gerrit Dou charged the price of a house for his rather artificial compositions. Few paintings were commissioned (although Vermeer had a patron). Hegel claimed ‘the final achievement’ of Dutch painting was ‘its utter absorption in the world and its daily life’. The new wave of Dutch genre painting emerged when painters like Gerard ter Borch (who delighted in white satin) peered into the sanctum of the home.

THE MEANING OF DUTCH PAINTING

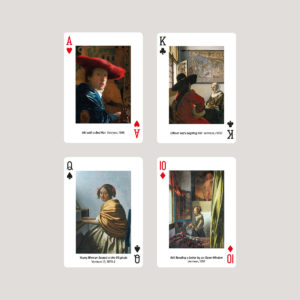

Joshua Reynolds, while admiring its surface skill, complained that Dutch art appealed to the eye only. But Ter Borch did more: he hinted at the uncertainties of bourgeois life, hidden meanings which Johannes Vermeer (1632-75) developed. Vermeer, probably self-taught, lived and worked in Delft and was twice ‘headman’ of its painters’ guild. Like Rembrandt he was a master of different themes; yet his true genius is revealed in his genre paintings, often pictures of ritualised courtship. However, there is another layer to such domesticity. In The Milkmaid (9§) two details reveal the girl’s compromised virtue – there is a Delft tile by the floor depicting Cupid and in front a footwarmer filled with glowing coals, a symbol of wantonness. Despite Vermeer converting to Catholicism (at the insistence perhaps of his wealthy mother-in-law), the Calvinist notion of restraint was a recurring theme. Maps, seen on Vermeer’s walls, signify worldliness (or union) and the spirit of investigation.

VERMEER’S ART

His paintings, mostly set in two small rooms in his house in Delft, look real but it is an illusion crafted by manipulating perspective; and by a low viewpoint that creates depth and lends stature and volume to the figures. Rodin noted that ‘an interior by Vermeer is a cubic painting’. Vermeer was innovative (and extravagant – he painted liberally with expensive ultramarine). He used an impasto technique to apply pointillés – globular dots of thick, coloured paint to convey the sparkle of light. He may also have used an optical device, a camera obscura.

His paintings, mostly set in two small rooms in his house in Delft, look real but it is an illusion crafted by manipulating perspective; and by a low viewpoint that creates depth and lends stature and volume to the figures. Rodin noted that ‘an interior by Vermeer is a cubic painting’. Vermeer was innovative (and extravagant – he painted liberally with expensive ultramarine). He used an impasto technique to apply pointillés – globular dots of thick, coloured paint to convey the sparkle of light. He may also have used an optical device, a camera obscura.

Vermeer’s oeuvre is 34 paintings. He was a busy art dealer (like his father, who doubled as a publican), as well as an artist; and his life was cut short. The ‘year of disaster’ destroyed him. His paintings were unsold. He feared for his family (his wife bore 11 children, though many died in infancy). ‘In a day and a half,’ his wife said, ‘he went from being healthy to being dead.’ Fashion deserted Vermeer, as it deserted Rembrandt and Frans Hals. He was forgotten, his works often credited to Pieter de Hooch (whose homely interiors and exploration of light influenced the younger Vermeer). But in the 19C Vermeer was rediscovered and revered anew for the luminous power of paintings that instruct, seduce and delight.