WOMEN AND ART

‘In the past a father would have died rather than let his daughter look upon a naked man’. So wrote Virginia Woolf in an introduction to her sister Vanessa Bell’s (1879-1961) paintings. In 1860, Marie Bracquemond (1840-1916), a student in Ingres’ studio, noted: ‘The severity of Monsieur Ingres frightened me… He would assign to [women] only the painting of flowers, of fruits, of still lifes…’ Bracquemond was fortunate – most women were excluded from academic training. The Paris École des Beaux-Arts admitted women only in 1897 (after much pressure), but they were banned from life classes. And etiquette meant they couldn’t travel, and observe, unescorted.

OBSTACLES

Marie Bashkirtseff (1858-84) wrote in her journal: ‘What I long for is the freedom to go about alone, to walk the old streets at night; that’s the freedom without which one cannot become a real artist.’ With its emphasis on contemporary life, and genre scenes, Impressionism suited artists like Berthe Morisot (1841-95), Manet’s sister-in-law, and the American Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), admired and promoted by Degas. But they could not have painted the lowlifes in Degas’ L’Absinthe or Lautrec’s brothel scenes. When she died, the critic CJ Bulliet dismissed Cassatt: ‘Like the vast majority of women artists Miss Cassatt preferred to be a lesser man.‘ A comment that ignored the sensitivity of her portraits. He would have agreed perhaps with Morisot’s tutor who warned her mother that a career in art would be ‘catastrophic’, given her genteel milieu. But both sides of the polemical fence can be crass. In what he called a ‘quantitative investigation’ an economist called Galenson recently ‘proved’ the greatness and pecking order of women artists by the number of illustrations of their work in modern textbooks. Cindy Sherman (b. 1954) came top. Helen Gørrill complained, in the London Guardian (2018), about Tate’s acquisitions policy: ‘Its diversity policy inadequately addresses gender… they seek only to collect works of art of outstanding quality.’

Marie Bashkirtseff (1858-84) wrote in her journal: ‘What I long for is the freedom to go about alone, to walk the old streets at night; that’s the freedom without which one cannot become a real artist.’ With its emphasis on contemporary life, and genre scenes, Impressionism suited artists like Berthe Morisot (1841-95), Manet’s sister-in-law, and the American Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), admired and promoted by Degas. But they could not have painted the lowlifes in Degas’ L’Absinthe or Lautrec’s brothel scenes. When she died, the critic CJ Bulliet dismissed Cassatt: ‘Like the vast majority of women artists Miss Cassatt preferred to be a lesser man.‘ A comment that ignored the sensitivity of her portraits. He would have agreed perhaps with Morisot’s tutor who warned her mother that a career in art would be ‘catastrophic’, given her genteel milieu. But both sides of the polemical fence can be crass. In what he called a ‘quantitative investigation’ an economist called Galenson recently ‘proved’ the greatness and pecking order of women artists by the number of illustrations of their work in modern textbooks. Cindy Sherman (b. 1954) came top. Helen Gørrill complained, in the London Guardian (2018), about Tate’s acquisitions policy: ‘Its diversity policy inadequately addresses gender… they seek only to collect works of art of outstanding quality.’

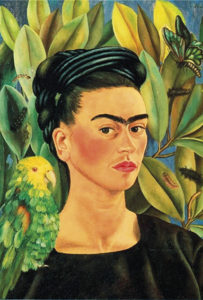

SURMOUNTING OBSTACLES

Some determined women surmounted social obstacles. Others raised two fingers. Laura Knight’s (1877-1970) Self Portrait of 1913 showed her actually painting a nude! ‘Vulgar’ the Telegraph called it. When the Swiss-born Angelika Kauffmann (1741-1807) was abused by the painter James Northcote, for having no ‘fist’, no ‘strength and muscle’ in her paintings, she paid a male model to sit for her. But delicacy meant no dangerous bits were exposed; and her father was always present. She was an international star and a founder member of the Royal Academy. Yet in Zoffany’s portrait of these academicians she is relegated to a fuzzy dot at the back. A few fathers were progressive, like that of Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842). He saw her youthful pastel portraits and announced – ‘You are to be an artist, my child.’ As a court painter she was briefly on the wrong side of history, but escaped the Paris Mob, just, and travelled around Europe before arriving in London in 1803 with diamonds sewn into her stockings to protect them from highwaymen. Reynolds rated her 1779 portrait of Marie-Antoinette ‘finer than Van Dyke’. Typically for the time, however, this forceful woman’s huge earnings were entrusted to her husband. He swindled her.

MUSEUMS AND WOMEN ARTISTS

The artist Hans Hoffmann said of a painting by Lee Krasner (1908-84): ‘This is so good you wouldn’t know it was done by a woman.’ An attitude that spawned the Guerrilla Girls. Formed in 1985, the group demonstrates (in gorilla masks for anonymity) against sexism in the arts. ‘Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?’ a 1989 poster shouted. ‘Less than 5% of artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.’ The art of the past was overwhelmingly male; museums reflect history. Yet there have always been women artists, whether anonymously creating the Bayeux tapestry or achieving fame against odds like Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c1656). Gentileschi, like so many women artists, came from an artistic family. She survived not just prejudice, but rape and torture. However, Camille Paglia disputed her iconic status among feminists because she painted ‘in a Baroque style created by men’.

The artist Hans Hoffmann said of a painting by Lee Krasner (1908-84): ‘This is so good you wouldn’t know it was done by a woman.’ An attitude that spawned the Guerrilla Girls. Formed in 1985, the group demonstrates (in gorilla masks for anonymity) against sexism in the arts. ‘Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum?’ a 1989 poster shouted. ‘Less than 5% of artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.’ The art of the past was overwhelmingly male; museums reflect history. Yet there have always been women artists, whether anonymously creating the Bayeux tapestry or achieving fame against odds like Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c1656). Gentileschi, like so many women artists, came from an artistic family. She survived not just prejudice, but rape and torture. However, Camille Paglia disputed her iconic status among feminists because she painted ‘in a Baroque style created by men’.

Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012) objected to the term women artists. ‘There is no such thing. It’s a contradiction in terms, like man artist or elephant artist.’ Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) agreed and added that there are only good artists and bad artists. Many of the best are celebrated in this deck, not for their gender but for their brilliance.